Why the Grand River Doesn’t Fully Freeze (and What That Tells Us)

Why the Grand River Doesn’t Freeze in Winter: How Flow, Frazil Ice, and Grand Rapids Shape the River.

On a winter morning in downtown Grand Rapids, the air can feel like it snaps. Sidewalks squeak under your boots. Breath hangs in front of you. And then you reach the Grand River with dark water gliding past snow-dusted banks, catching the light as it ripples through the faster spots.

It feels like the river should be frozen solid.

But most winters, the Grand River doesn’t freeze like a pond. It keeps moving and changing, ice hugging the edges, broken pieces drifting by, slushy patches that show up and disappear overnight. That’s not random. It’s a mix of nature and the way people have shaped this river over time.

Along the Grand Riverfront during the winter season. Photo credit: Experience Grand Rapids

The Simplest Explanation

Here’s the simplest reason: moving water is hard to freeze. A pond can turn into a smooth sheet because the water sits still, while a river is always stirring itself. Ice formation mostly comes down to two things: temperature and turbulence. Temperature is obvious, we feel it. Turbulence is just the river being rough and choppy. That roughness keeps mixing the water, bringing slightly warmer water up from below and breaking up ice as it tries to form.

Sometimes the first ice you see isn’t a sheet at all – it’s more like tiny crystals swirling in the current. The National Weather Service calls this “frazil ice,” ice that’s “formed in super-cooled, turbulent water.” If you’ve ever looked down from a bridge and thought, ‘Why does the river look slushy?’ that’s probably what you were seeing.

Movement & Man-Made Causes

Downtown Grand Rapids has another big factor: the Grand River is a strong river with serious flow. United States Geological Survey measurements at the Grand River often show water moving in the thousands of cubic feet per second. Fast-moving water usually means more stirring and less chance for a solid “lid” of ice.

And then there’s the city side of the story. Grand Rapids’ Water Resource Recovery Facility treats about 40 million gallons of wastewater every day before it goes back to the river. The warming effect can change depending on conditions, but United States Geological Survey research in other cities shows treated water released into rivers can make winter water temperatures warmer downstream.

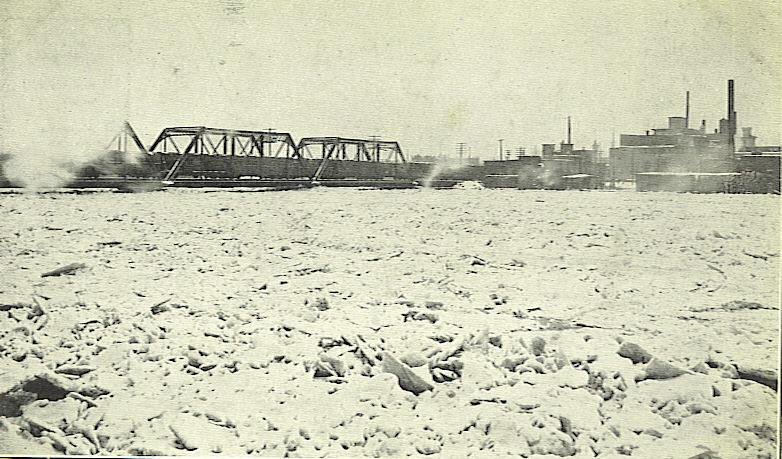

The Grand’s winter habits even carry a little history. The City of Grand Rapids Archives describes past ice jams, often near bridges, and a hard-to-believe fix from another era: dynamite. Ice has always been beautiful, but it can also be dangerous when it piles up and blocks the flow.

The GR& Challenge

So next time you’re on the riverwalk, try this GR& winter challenge: stop for two minutes and watch. Where is the water calm enough for ice to hang on? Where is it racing too fast to freeze? The patterns are the river talking: about how it moves, how we’ve built around it, and how Grand Rapids & the Grand keep shaping each other, season after season.